Before we get into the how, let’s talk briefly about why you should be incorporating some kind of squat variation into your gym routine if you’re not already doing so.

The squat is a compound exercise, which means it involves movement at multiple joints in the body, requiring a number of different muscle groups to be active. Your quads, hamstrings, adductors, abductors, glutes, calves, hip flexors and extensors, and most of the muscles in your back and core will all be engaged at some stage during the movement.

The Benefits Of Squatting

Why is this a good thing? Well, the more muscles you engage in any given exercise, the greater the energy demands and the more acute the hypertrophic stimulus will be. That’s why squats are generally considered the cornerstone of any muscle building gym programme. Not only will they help you accumulate muscle mass in your legs, but they will also help you make gains in the upper body department too. That’s how much of an impact they have on your bodies general muscle building capacity, providing the perfect anabolic environment through the release of testosterone and human growth hormone.

So, if you’re working out in the gym to maintain your general health and fitness, to look good on the beach, or to support your participation in sports like football, rugby or field hockey, then some form of squat pattern really is a must. The movement is highly functional and translates into a wide range of everyday activities as well as sporting actions, helping to protect against injury and improve efficiency.

Introducing squat patterns into your regular workout doesn’t necessarily mean loading up a barbell with the heaviest plates you can find in the gym. Don’t get me wrong, the barbell squat is probably the most fundamental of all the variations and a great exercise if you’re looking to make strength gains. However, there are so many options for you to choose from, many of which you don’t even need a gym membership to perform. On holiday or travelling for work so you can’t make it to a gym? That doesn’t mean you can’t squat. Double leg, single leg and bulgarian bodyweight squats are a great way of introducing the squat pattern into home workouts and don’t require any equipment at all.

The How?

The advice which follows relates to barbell squats and its variations. This is the most fundamental of all the squat patterns and arguably the most effective at producing strength and hypertrophy developments.

The Setup:

Before you even begin the actual squat movement, there are a few basic setup principles you need to get right to make the exercise both safe and efficient. These pointers address factors such as where the bar is placed on your body, your hand and wrist position and stance width. Most are personal preference within set parameters, which involve you achieving body positions which are comfortable for you!

1. Bar Placement:

Back squat

For the purposes of this article we are going to consider two different bar placements, one for the back squat, and one for the front squat. For the back squat, the bar should rest across the bulk of your trapezius muscles. In my personal experience this is the most comfortable positioning. Whilst some advocate a slightly lower base of support (with the bar resting on the rear deltoids), which will produce a slightly different movement pattern and thus emphasise slightly different muscle groups, the differences are marginal and as the load increases I find the higher position more stable.

The most important factor to consider in the high bar position outlined above is to avoid the bar making contact with the bony bump at the base of your neck (C7) which can cause discomfort and ongoing neck pain.

Front squat

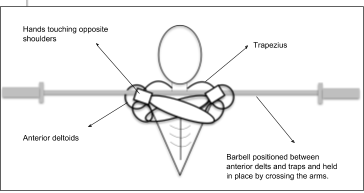

If you’re new to front squatting then finding a comfortable and stable bar position can be challenging. I find resting the bar between your anterior deltoids and the front of the trap (the little hollow just above the clavicle) the best option. Unfortunately, this remains a pretty uncomfortable position and you’re likely to get some bruising when you first start.

2. Hand positioning:

Back squat

The narrower your hand position the better as it will help you maintain a more stable back position. I normally set my hands just a little outside shoulder width, which will cause your scapulae to retract slightly, and force your lower traps and rhomboids to contract, all of which helps generate some good tension in the upper back.

Front squat

There is slightly more variation in the hand position for a front squat, which is normally as a result of the individuals shoulder and elbow mobility.

- Standard– if you are capable then this is probably the best position to adopt. With your fingers pointing towards you and your elbows facing forwards and as high as possible, you want your hands slightly wider than shoulder width apart with as many fingers in contact with the bar as possible.

- Arms crossed– after positioning the bar as explained above, simply cross your arms. Touch each shoulder with the opposite hand and secure the bar between your arms and anterior deltoids. This is a particularly useful position if you lack the shoulder and elbow mobility to achieve the standard position. The image above outlining the placement of the bar for the front squat also shows a textbook arms crossed positioning.

- Straps– this is a great happy medium for those lacking in shoulder and elbow mobility but want to progress towards achieving the standard hand positioning outlined above. Wrap the straps tightly around the bar a little wider than shoulder width and grip them with your hands in a neutral position as close to the bar as possible. This should allow you to reach a higher elbow position than you are otherwise capable of achieving. This is probably a preferable option to the crossed arm position when the load begins to increase as it is more stable.

3. Wrist positioning:

Back squat

The position of your wrists shouldn’t be too much of a problem during a back squat. The weight should be supported pretty much entirely by your traps and rear deltoids. Keep your wrists in a neutral position so as to avoid causing yourself wrist pain. If you are unable to do this then it is likely that the position of the bar is incorrect and you are not creating a proper base of support.

Front squat

Wrist position is normally much more an issue with the front squat. The traditional front squat position will be problematic if you have poor mobility or lack a stable base across your anterior deltoids and the front of your traps. In all honesty, the easiest way to solve this problem is by using the crossed arm position or by utilising lifting straps, both of which take the wrist position out of the equation.

4. Elbow position:

Back squat

Elbows should be as close to your ribcage as possible.

Front squat

A high elbow position will help prevent your thoracic spine from flexing and should also encourage a more stable base for the barbell as a result of the resulting tension in your anterior deltoids.

5. Stance width:

The distance between your feet when squatting is largely personal preference and should be determined by what is most comfortable for the individual. The best place to start is probably shoulder width, moving your feet slightly wider or narrower depending on what works best for you. Perform the squat pattern from a number of different stance positions and see how deep you can squat whilst maintaining a neutral spine. Generally speaking, if you lack mobility at the hips then a wider stance will help negate this as well as making the lift slightly easier on your back.

With differing stance widths comes slight adjustments to the angle at which your feet are placed (toes pointing straight forward or slightly outwards). In general, the wider your feet are apart then the more hip abduction there will be and the more your knees will naturally point slightly outwards. Because you want your knees to move in line with your toes you will need to adjust the angle at which your feet point. My advice would be to see which feet positions feel most comfortable and which allow your knees to track over your toes. There is no point in squatting with a predetermined foot angle you’ve read about online.

6. Tension:

The more tension you can create throughout your entire body, the more control you will have over the squat movement. In addition, you will be working more muscles at a greater intensity which will help you burn calories and make strength and hypertrophy gains. There are a few really simple ways you can help yourself achieve this tension:

- Once you are confident with your foot position, plant your feet firmly and attempt to rotate your hips outwards. The best way of doing this is by trying to pull your heels towards one another and push your toes away from each other. In relation to your left foot, for instance, that means pulling your heel in to the right and pushing your toes out to the left. Your feet will not actually move anywhere because they must remain in contact with the ground but the intention itself will create the tension in your legs and core that you’re looking for.

- Imagine you are standing on a sheet of paper which you are trying to rip in half using only your feet. This will help engage your glutes properly and should also help prevent your knees from collapsing inwards.

- You will naturally generate tension in the upper back with your bar placement, hand and elbow positioning. The best way of increasing this during a back squat is to attempt to bend the bar across your shoulders as if you are trying to fold it half. For a front squat drive your elbows as high as you can.

Breathing:

Something that even the most experienced athletes often neglect during their training. The ability to breathe effectively can have a significant impact on your capacity to squat safely and efficiently. Breathing correctly should help you keep your torso rigid and in a good position throughout the squat pattern.

As you are about to enter the descent phase of your squat, take a deep breath into your stomach causing it to expand. Tense your abdominal muscles and squeeze your glutes at the same time. All of this should pull your rib cage down slightly and tilt your hips forward a smidge. This will help you create the neutral spine position, which is vitally important for performing the squat movement safely, from the outset. This factor becomes increasingly important as the load on the barbell increases and the risk of injury becomes that much greater.

Eccentric phase:

There are 2 basic ways in which you can initiate the eccentric (or lowering) phase of the squat pattern.

- The first method is by folding at the hips and knees simultaneously, dropping your bottom down directly between your heels. This technique will generally allow you to reach a deeper range of movement which is commonly believed to translate into a more significant training effect. However, if you have limited ankle range, then this can be a difficult movement for you to perform. Ankle tightness may prevent your knees from continuing to move forward as you lower, naturally forcing you backwards into the position described below.

- The second method is by folding at the hips before the knees, pushing your bottom backwards as if you were trying to sit on a chair placed behind you.

Speed of descent

Provided you are in full control of the bar, then the faster the descent the better. The more momentum you carry into the bottom of your range, the more ‘bounce’ you will be able to achieve thanks to the stretch reflex of your muscles. This will all contribute to you being able to shift heavier loads and make more significant strength gains. If, however, your session is focusing more heavily on building muscle, then it has been suggested that a slower and more deliberate eccentric contraction will generate more hypertrophic stimuli. In which case, you really need to slow your descent down.

Range

Most research suggests that the greater the range of motion you can achieve whilst squatting, the greater the training effect. Consequently, you should go as deep as you are capable whilst maintaining a neutral and safe spine position.

Concentric phase:

The best way to initiate the upward phase of your squat is by simultaneously driving your traps into the bar and your feet into the ground. As you begin to move in an upwards motion try to get your hips under the bar whilst pushing your chest forward. For the greatest gains during the concentric phase you need to be moving the bar as quickly as possible. If the load is heavy then realistically it isn’t going to be moving anywhere particularly fast but it’s vitally important that the intent is there nonetheless.

Keeping your core tensed and maintaining pressure in your trunk on the way up will help you to maintain that all important neutral spine position throughout.

When you reach the top of the range be sure to fully extend your hips and squeeze your glutes so you garner every ounce of muscle recruitment from the exercise.

The video below above gives a great outline of the basic squat technique and some all important visual guidance to the written explanations in this article.

Common mistakes:

- Without doubt the most common issue I see in the gym, in any exercise, is a rounding of the back at some point during the squat pattern. This flexed position puts a huge amount of stress on the lower back, in particular when the load on the barbell begins to increase. That’s why it’s something you really need to nail before you start shifting some serious weight. You do not, however, want to overcompensate by putting your spine into a position of extension as this can cause lower back pain too. A nice neutral and natural back position is what we’re looking for here and for me is probably the single most important aspect to ensure you have right before you start any squat movement.

- Pushing the hips back too far at the beginning of the descent. This is generally caused by folding at the hips long before the knees and will result in the bar moving in front of your centre of gravity and putting the weight over your toes. The easiest way to fix this problem is to fold at the knees at the same time as the hips, allowing you to drop your bottom directly between your heels in a straight vertical line.

- If you’re heels don’t remain in contact with the floor at all times then there is likely 1 of 2 problems which can be easily remedied. Either you are breaking at the knee way before the hip, i.e. the opposite of the above mistake, or you have poor ankle and calf mobility. If it’s the former, then simply concentrate on folding at the hips and knees simultaneously and if it’s the latter then you need to foam roll and stretch your calves and the bottom of your feet (plantar fascia) in order to improve your mobility. If this doesn’t do the trick then you can place 2.5kg plates under your heels which helps take ankle mobility out of the equation.

- If your knees collapse inwards towards the middle of your feet during the eccentric or concentric phase of the squat pattern then you are likely to cause yourself some harm over an extended period of time. This problem is most commonly caused by a failure to engage the glute muscles properly. The easiest way to counteract the tendency to collapse is to imagine you are trying to pull a piece of paper apart with your feet as explained earlier in the article. In addition you could introduce a glute specific warm up drill before you start your barbell squat. Place a resistance band around your knees and perform a series of bodyweight squats. The band will force you to push out with your knees against the resistance, helping to properly engage your glutes.

- As hard as it might be to believe, so many people position the bar unevenly across their backs. This is actually surprisingly easy to do, particularly if you don’t have a mirror in front of you. The more uneven the bar, the more weight will be shifted to one side, which can lead to rotation and uneven development. The easiest way to solve this problem, in all honesty, is to concentrate a little more. If you have a training partner or a spotter they should be able to help too!

- Failure to achieve sufficient depth, whilst not necessarily a mistake, is a common trait which will reduce the training effect of your squat pattern. You should definitely not push your range of movement beyond the point you can reach safely (i.e. whilst maintaining a neutral spine position). However, if you begin the concentric phase of the lift before your hips have at least reached parallel with your knees and it’s not because of back flexion or a lack of hip, knee or ankle mobility, then you’re cutting your reps shorts for no good reason.

- Whatever you do, don’t exhale too soon. Holding your breath as you move through the concentric phase of the lift will help you maintain the intra abdominal pressure we’ve already discussed as being vital during the eccentric movement. This tightness in your torso will help keep you strong and prevent any potential back related issues.

Jacky has a degree in Sports Science and is a Certified Sports and Conditioning Coach. He has also worked with clients around the world as a personal trainer.

He has been fortunate enough to work with a wide range of people from very different ends of the fitness spectrum. Through promoting positive health changes with diet and exercise, he has helped patients recover from aging-related and other otherwise debilitating diseases.

He spends most of his time these days writing fitness-related content of some form or another. He still likes to work with people on a one-to-one basis – he just doesn’t get up at 5am to see clients anymore.